Trendy Fads and Irrational Decisions: An Age Old Curse of the Human Mind - Published on Medium, July 2019

Trendy Fads and Irrational Decisions: An Age Old Curse of the Human Mind

Caprice (n): a sudden and unaccountable change of mood or behavior

Caprice is a funny word I only discovered in my final semester studying philosophy, a semester in which I happened to be reading a lot of things written in the 18th century. This, it turns out, is no coincidence. Google’s convenient chart of the word’s usage shows a massive ballooning of its popularity in the late 1700s (when English speaking philosophers presumably anglicized the Italian and French word “capriccio”), followed by a sharp decline in the subsequent century. Ironically, it appears that the English speaking world’s time with the word caprice was in fact capricious — a fad, a dated mark of a specific era.

In nearly all of the cases that I encountered this word in a philosophical text, it carried a negative connotation. This, the 18th century, was an era of idealism. There was no room for sudden changes of behavior and thought. The ultimate, all encompassing, perfect truth of reality did not wax and wane with the fashions of the age.

Friedrich Schiller is most well known as a playwright, but his On the Aesthetic Education of Man, a series of flowery letters to his patron of the time hailing the importance of art to humanity, has gone down as a classic work of 18th century aesthetic philosophy. In his idealistic mind, the true artist takes their inspiration not from the random happenings of her irrelevant place in history, but from some pure, timeless well of truth that remains constant through all times. (Which to him and so many of his Grecophile contemporaries was most properly represented by Ancient Greece.)

“No doubt the artist is the child of his time, but unhappy for him if he is its disciple or even its favourite. Let a beneficent deity carry off in good time the suckling from the breast of its mother, let it nourish him on the milk of a better age, and suffer him to grow up and arrive at virility under the distant sky of Greece. He will, indeed, receive his matter from the present time, but he will borrow the form from a nobler time and even beyond all time, from the essential, absolute, immutable unity. There, issuing from the pure ether of its heavenly nature, flows the source of all beauty, which was never tainted by the corruption of generations or of ages, which roll along far beneath it in dark eddies. Its matter may be dishonoured as well as ennobled by fancy, but the ever chaste form escapes from the caprices of imagination.”

Schiller and the like minded thinkers of his age railed against caprice. For them, it was a bad word, an impure influence with no rightful place in any serious work of art, philosophy, or politics. These sons of the Romantic era had grand ideas of Beauty with a capital B. Strange and seemingly arbitrary fashion trends could only serve to contaminate it.

Voltaire on Caprice

“After the earthquake, which had destroyed three–fourths of the city of Lisbon, the sages of that country could think of no means more effectual to preserve the kingdom from utter ruin than to entertain the people with an auto–da–fe, it having been decided by the University of Coimbra, that the burning of a few people alive by a slow fire, and with great ceremony, is an infallible preventive of earthquakes.”

Candide is a hilarious satirical novel authored by Voltaire in the later half of the 18th century. As with all great satire, he draws attention to the irrational injustices of his day by highlighting their hypocrisy with humor. In this passage, he explains how, following a massively destructive earthquake, the Spanish government appeases its naturally restless population with public burnings of those guilty of some (in some cases shockingly minor) crime under the guise of it being preventative of future disaster. Although Candide is fictional, this part of the story is inspired by a true event, and unfortunately it is far from the only of its kind.

History is full of instances of disaster being co-opted to advance some agenda that couldn’t garner adequate support in more uneventful times of peace. There is good work in psychology and neuroscience that prove that no meaningful decision can be made without some presence of emotion in the decision maker. Disasters are great conduits of emotion, and savvy leaders know this. They bring a great infusion of capricious passion into the population that clouds our better judgement and incites inadequately considered action.

Caprice in America

The Radiolab episode, “60 Words,” is a history of the composition, ratification, and consequences of the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), a proposal signed into law just one week following the exceedingly emotional 9/11 attacks. The 60 words that serve as the operative element of the short bill essentially granted to the President unilateral power to authorize violent attacks of foreign targets with very little oversight. Although it may have come to being under good intentions, it has been responsible for a radical expansion of executive power that has led to a nearly 20 year war and a slew of suspicious drone strikes, Navy SEAL raids, and the establishment of the infamous prison camp at Guantanamo Bay.

“That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons.”

Given their immense impact and controversy in the present day, it may come as a great surprise to many that these 60 words were met with almost no opposition at the time that they were proposed to Congress in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. In fact, there was exactly one member of Congress who voted against the AUMF: California Representative Barbara Lee.

In her prophetic defense of her decision she warned that the law may lead to an unacceptable level of executive power and an everlasting war with no exit strategy. As the sole detractor, her opposition to the bill attracted intense media attention. She was bombarded with angry messages and death threats from maniacal citizens hellbent on avenging the most deadly terrorist attack in American history. She stood her ground though and continues to speak against the AUMF to this day. In addition to her political misgivings, she points to a simple principle of psychology in support of her decision.

“I knew it was an emotional moment. The first rule of psychotherapy 101 is that you don’t make decisions where you’re emotional or angry. You wait and think it through. You don’t just respond when you’re in that kind of emotional state.”

If Schiller were alive to comment on the issue, he would praise Lee’s admirable immunity from caprice. In some cases though, it can be impossible to avoid reaction to the events of one’s time in history. Even philosophers are subject to the shifting tides of caprice.

Caprice in Nazi Germany

Edmund Husserl is a German philosopher best known for officially establishing the field of phenomenology: the detailed study of consciousness and experience. Martin Heidegger arrived at Husserl’s university just as the elder was mourning the death of his son, who happened to be Heideggers’s age. This, and his exceptional promise as a budding phenomenologist caused Husserl to develop a deep affection for Heidegger. The Husserl family considered him an adopted son.

Husserl and Heidegger were both German, male, phenomenologist philosophers who considered themselves a part of the same family. Given their inherent similarities, it is a great testament to the powerful winds of caprice that it blew them in entirely opposite directions at the time of the Nazi party’s rise to power.

Hitler exposed a fundamental difference that drove a wedge between them — a difference that is not necessarily reflected in their philosophies, which for both of them were constantly evolving and somewhat mysterious. Husserl loved the imagery and idea of cultures encountering one another. When ancient traders stumbled upon a new world, they experienced a profound revelation: “There are other ways to live, the one I’ve always known is just….mine.” This puts one into a questioning mode where nothing is taken for granted: the perfect non-capricious state of mind for doing philosophy and making progress. He (another Grecophile) thought Ancient Greece was the ultimate place of philosophy because they had so much interaction (in trade and war) with other civilizations. Husserl thought that Hitler could and should be defeated through a unification of the world’s nations, through a free, international, consciousness expanding exchange of ideas. The capricious crises of the 1930s moved Husserl to expand his mind out into the world around him. It did the opposite to Heidegger.

Heidegger, like Husserl, Schiller, Nietzsche and everyone else, had an Ancient Greece fetish, but unlike the others he felt that Greek philosophy was ruined by the “worldliness” of Socrates and Aristotle. A true hipster, for Heidegger, Greek philosophy was only worthwhile in the era of the pre-Socratics with their poetic, metaphysical, and archaic style. He wanted to shrink, not expand. His reaction to the bubbling troubles of Europe was to retreat into himself and into his own nation. Martin Heidegger joined the Nazi party in May of 1933 and remained a member until the end of World War II. This was a revolt against globalism and a revolt against himself. He had pioneered the phenomenology of cooperation and “being-with-others.”

Does anyone really have a consistent set of metaphysical, political, and personal beliefs that last a lifetime? Is anyone, even a legendary thinker, safe from being swept up in the capricious forces of their life: their health, love life, and proximity to war? Maybe Schiller’s mandate is unrealistic. Caprice is a fact of life.

Caprice in Art

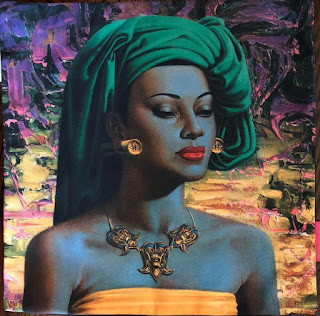

Kitsch is a genre of art that Schiller should be thankful he never lived to see. It is pure caprice: a fad formed as a reaction to another fad which used fads as its subject matter and aesthetic style. Clement Greenberg, an American art critic defined kitsch in a famous essay from 1939.

“Where there is an avant-garde, generally we also find a rear-guard. True enough — simultaneously with the entrance of the avant-garde, a second new cultural phenomenon appeared in the industrial West: that thing to which the Germans give the wonderful name of Kitsch: popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc, etc.”

Kitsch can survive as a captivating genre of art because it speaks to and celebrates the reality of an undeniable element of the world we inhabit: caprice. It’s easy to see the destructive potential that unhinged caprice can wreak on a mind or a society, but it’s not something that one can realistically hope to eliminate from their lives entirely. Flying away to be “beneath the skies of Greece” sounds nice, but what good can you do ignoring the world for a weird self-constructed fantasy?

There is some happy medium, some middle ground between endless, impassioned, crazed opinions on the 5 day news cycle and a useless monastic detachment from the world. Caprice and kitsch are funky, fun, and quirky. Romantic idealism is steadfast, timeless, and strong. Without a stubborn sense of tempered, non-capricious commitment to ideals, we have made some of our most perplexing and ill-advised decisions, like supporting Hitler, granting dictatorial powers of war-waging, and burning innocent people publicly to fend off a natural disaster. But without a dash of caprice, we are out of touch, rigid, and boring.

Comments

Post a Comment